Education Day

- Celebrate the Culture of Plants

- Cooking Demos

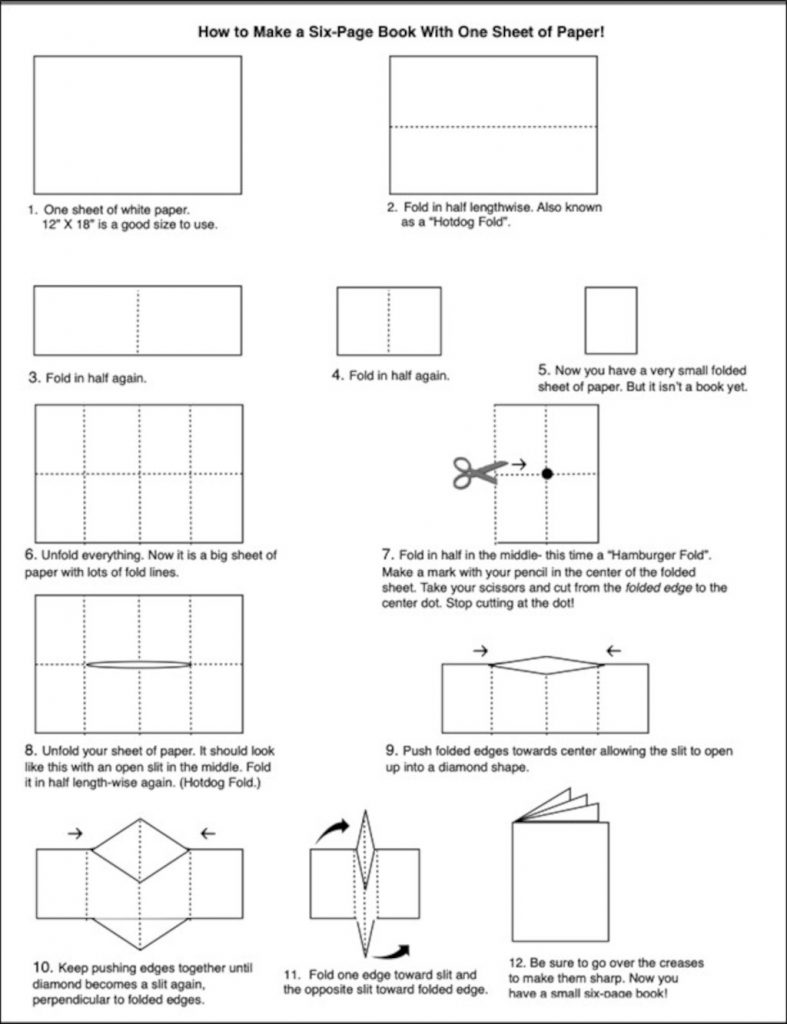

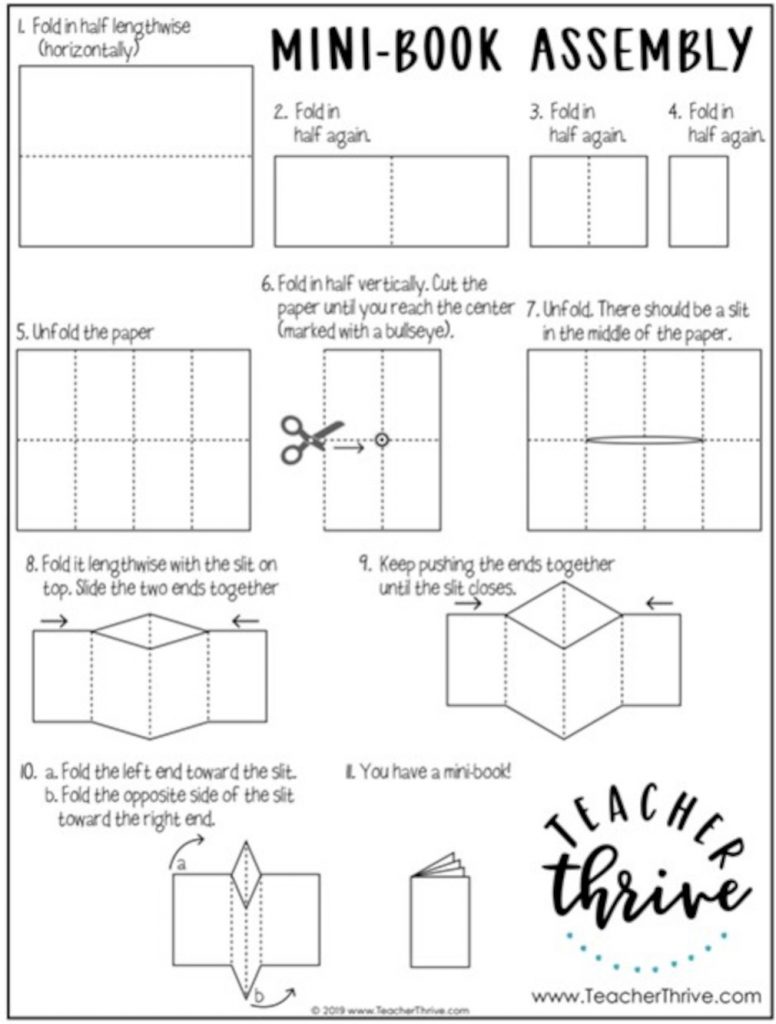

- Passport Book

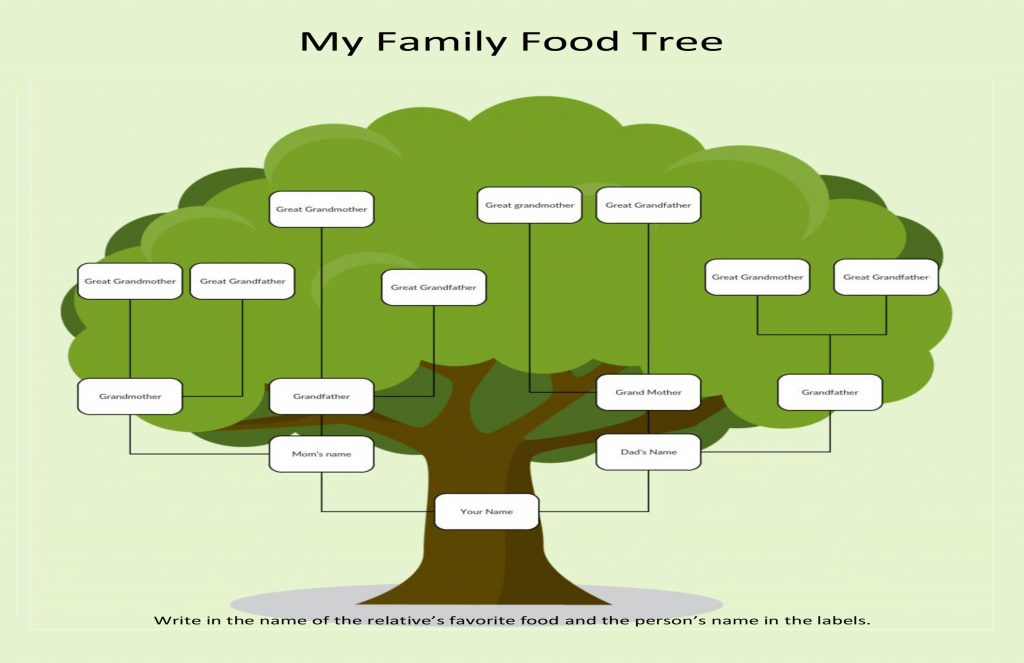

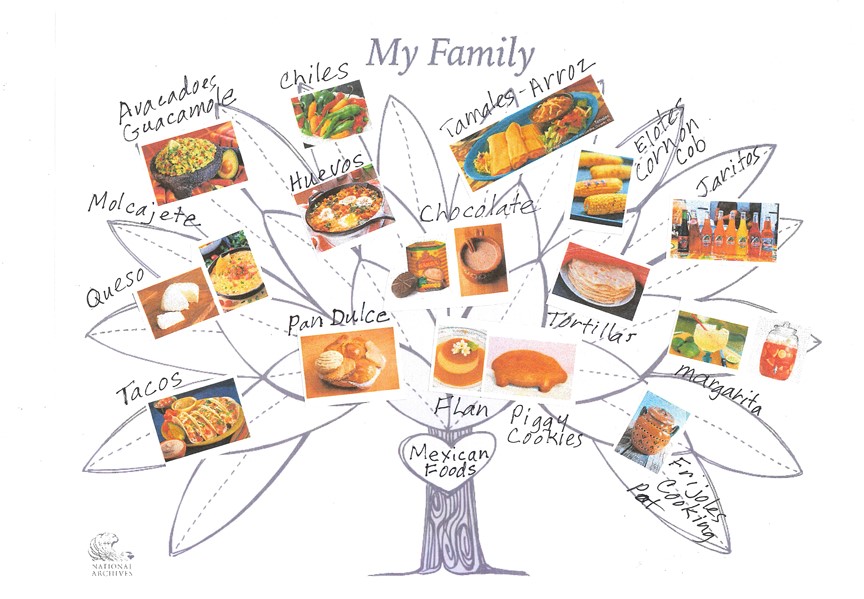

- Family Tree Story Genealogy

- Stamp Collecting

- Japanese Origami

- Stone Soup

- Traditional Foods

- The First People and The Hoop Dance

- Lithuanian Straw Ornament

Celebrate the Culture of Plants: The Seeds of Heritage

77th Holiday Folk Fair International’s theme is Celebrate the Culture of Plants: The Seeds of Heritage. Plants are life. They produce almost all of the oxygen we breathe and make up 80 percent of the food we eat. Even the meat, fish or dairy products we eat come from animals that depend on plants to grow. They all start with a seed.

The 2020 International Year of Plant Health increases awareness of the importance of healthy plants and the necessity to protect them. Plants are all around us. Their relationship with humans is a long one, so it is not surprising that people have always admired them and have had a special connection with them. This relationship is sometimes so strong that people turn to plants to honor some of the most important moments in life: birth, marriage, death. Plants are also used in many cultural ways – in medicine, as religious objects, as subjects in mythology, as food and shelter and in many festivals, celebrations, and traditions. Herbs and spices are used primarily for adding flavor and aroma to food and some are used as a preservative. Herbs are obtained from the leaves of plants and spices are obtained from roots, flowers, fruits, seeds or bark.

One of the most fundamental human experiences is agriculture; we plant healthy seeds and nurture the healthy seeds. We provide nutrients and combine them with water and sunlight. The plants we grow provide our basic needs in shelter, food, medicines and clothing. We need to care for and nurture the plants in our world. Can you imagine a world without plants? Likewise we become culture keepers safeguarding our culture; it is necessary to create a thirst in the next generations to learn about our cultural heritage, value it and enjoy it.

The origin and history of our plants play a vital role in defining the culture of a region. Plants contribute a key element in our food, clothing, work and life. The connections between local customs and traditions and plant are linked to that a specific geographical area – the development of its cuisine and the telling of the stories of the cultivated plants; this safeguards the living heritage of each plant in its unique cultural context.

The largest plants on earth are trees. They provide fruit, nuts and spices, chocolate and coffee, wood and materials for products such as making paper, maple syrup, chewing gum, rubber, crayons, paint, soap, dyes, medicines, cosmetics. They help reduce pollution, release oxygen into the atmosphere, absorb carbon dioxide slowing down the rate of global warming. They reduce wind speed and cool the air as they lose moisture and reflect heat upwards from their leaves. This helps prevent flooding and soil erosion. Not only are trees essential for life, but is the longest living species on earth, they give us a link between the past, present and future.

Immigrant, refugees, asylees – people from around the world have made Wisconsin their home. They bring with them their use of plants that are unique and meaningful to them. These plants bring them together as they celebrate their traditions, their stories, their music and songs and dances. Plants are a precious link to the past and to the future – to traditions and celebrations of everyday life. These traditions are celebrated in the Holiday Folk Fair International.

Festivals pass on tradition and pride from one generation to the next. From its beginning Holiday Folk Fair International’s central focus has been education presenting cultural heritage through dance, music, food, traditional outfits and exhibits. The Holiday Folk Fair International continues its dedication to build cultural and ethnic understanding. The festival brings together more than fifty culturally diverse ethnic groups – each with its own unique history and heritage. These groups work together to present the largest, oldest indoor multicultural festival in the United States. This annual event allows the communities to share their heritage in a welcoming environment that honors their culture, deepens pride in their own culture and develops mutual respect for their own culture and the culture of others.

For 77 years, the Holiday Folk Fair International has been a keeper of our rich and diverse living cultural heritage, safeguarding the past, honoring the present, embracing the future. People share their intangible cultural heritage – the knowledge of traditions, skills and customs that are transmitted to the community, from generation to generation and to other communities. This contributes to social cohesion, encouraging a sense of identity and responsibility which helps individuals to feel part of one or different communities and to feel part of society at large.

During the virtual Holiday Folk Fair International, 2020, the honored food is food from plants.

Honoring Culturally Significant Plants

Plants are all around us. Their relationship with humans is a long one, so it is not surprising that people have always honored plants and had a special connection with some of them. This relationship is sometimes so strong that people turn to plants to honor some of the most important moments in life: birth, marriage, death. Plants are also used in many ways – in medicine, as religious objects, as food, in festival, celebrations, and traditions. Some plants represent a country as its national symbol, such as the leek for the Welsh and the maple leaf for Canada. Although it could be said that all the plants are culturally important, here is a sample of some culturally significant plants from around the world.

- Tea originated in Asia. It was grown in China for several thousand years before being cultivated in other parts of the world. In England, everybody loves to have a “tea break” in the afternoon, and in Japan, special tea-drinking ceremonies are an important cultural tradition.

- Rice is not just food; it also holds both historical and contemporary meaning. Rice has been for more than 2,000 years and is present in many aspects of life – in everyday meals, in New Year celebrations, and in family rituals.

- Henna is a shrub that grows in warmer climates all over the world. It has been used to make a paste for painting the body for thousands of years. Symbolically, henna paintings are not permanent – just like life. This temporary body art are part of weddings, baby blessings, holidays & birthdays in many cultures in South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

- The Marigold flowers are orange-yellow in color and they are popular garden flower in India and used during weddings and celebrations where they are known as the herb of the sun. They were also sacred to Mayan, Aztec and Mayan cultures, the plant was often used to honor gods and spirits. In Mexico, marigold flowers is used during the Dia de los Muertos – Day of the Dead to celebrate and honor the lives of friends and families who have passed away.

- The Shamrock is a clover known as the national flower of Ireland. Mentioned in mythology, the shamrock is believed to have been used in ancient ceremonies. Stories say that St. Patrick used the shamrock in his teaching of Christianity. It is used as a logo for many products, and it is said to bring good luck to anyone who grows it!

- Holly is best known for its use in Christmas decorations along with such plants such as ivy and mistletoe.

- Lucky bamboo is beautiful and sought after, especially during the Chinese New Year. There is a belief that one stem brings good fortune, three stems bring happiness, five bring health, seven bring wealth, eight bring prosperity, and 21 bring general good blessings.

- The Three Sisters are the three main agricultural crops of various indigenous peoples in the Americas – winter squash maize or corn and climbing beans. These three crops benefit from each other. The maize provides a structure for the beans to climb. The beans provide nitrogen to the soil for the pants and the squash spreads along the ground, blocking the sunlight preventing the establishment of weeds. The squash leaves also act as a “living mulch“, creating a microclimate to retain moisture in the soil, and the prickly hairs of the vine deter pests.

There are many plants that tell us their stories and play important roles in people’s lives – the use of tobacco by Natives Americans, palm for Palm Sunday, evergreens for Christmas Trees, pineapples as a symbol of hospitality.

Plants provide nutrition, are harvested for medicinal uses, create dyes to be used to stain fabric, writing or drawing. The fibers are used to weave baskets and clothing. They are used in dances such as the Filipino Tinikling bamboo poles, American Indian rattles, Hawaiian adornments plants and flowers, West Indian musical rattle seedpods.

Traditions of farming and gardening, of cooking and sharing food, of using plants for treating illness and maintaining health are important elements of our identity. For the displaced community such as refugees, plants are living cultural heritage – cultivating them create links to their homelands and a sense of their heritage.

Click Here for a Sample Passport Book

Stamp Collecting

Stamp collecting is an interesting and fun hobby that has no age limits or ability. It is easy to make friends with other people who share the love of collecting. Starting a stamp collection will introduce you to people and places around the globe. It is a way to explore the world, its many different countries, their diverse history, beautiful artwork and cultures.

It is easy to begin a collection. Cut the stamp out of the envelope from everyday mail – leaving a tiny paper margin around the outside edges of the stamp. The used stamp can now be hinged or mounted on the album page.

Getting Started – Acquiring Stamps

Getting started on a new stamp collection can be exciting and fun. There are a number of ways to start finding stamps. Ask your family and friends to save the stamps they get on their incoming mail. They can save the whole envelope or they can cut out the stamp portion. You can also ask them if they have any old letters or postcards that you could have.

Ask businesses, institutions, and organizations to save the stamps that they get on their incoming mail.

Visit a stamp club such as Milwaukee Philatelic Society or the Wauwatosa Philatelic Society. For additional Wisconsin stamp clubs, visit the Wisconsin Federation of Stamp Clubs website at www.wfscstamps.org.

American Topical Association (ATA) offers beginning topical kits with stamps, album pages, hinges, and instructions for about $7.00. See https://americantopical.org/Taste-Of-Topicals-Info.

You can buy a large starter package of stamps online or from a stamp dealer. You may also buy items at stamp fairs, online trading sites, and thrift shops.

By looking through a catalogue of stamps, you can see what kinds of stamps you like and would like to collect. Some people like to collect stamps from certain countries, from a period in history, animal stamps, celebrity stamps, presidents stamps, etc. You can find your own favorites and begin your own collection.

Sorting and Organizing Stamps

Some ways to sort postage stamps:

- Sorting stamps according to topic such as space, baseball, dogs, birds, etc.

- Some philatelists became interested in collecting stamps from a single country. This is called a one country collection.

- Classifying stamps according to commemoratives.

- Classifying stamps according to definitive issues.

Soaking to Remove Envelope Paper

Do not remove a stamp from an envelope or its paper backing by pulling it, as this will cause irreparable damage. Use a pair of sharp scissors to trim the paper (about ¾ in. around the stamp.) It is much easier to handle stamps when they are attached to an envelope and to sort them before you soak them, which will make them delicate.

How to soak stamps – not for self-adhesive stamps:

- Pour clean warm water into a shallow bowl and float each stamp (with the design facing upwards) on the surface.

- Float as many stamps as you can accommodate at any one time.

- Leave for 10 to 15 minutes so the water can impregnate the gum which is making it stick to the paper.

- Use your fingers to gently peel the stamp away from the paper. If it does not come away easily, leave to soak for another five minutes before trying again.

Stamps damage easily when they are wet or damp. Do not use tweezers or stamp tongs at this stage or you could ruin them.

Soaking water can quickly become sticky or clouded with gum adhesive and it is a good idea to change it for every batch of stamps.

How to Dry Stamps:

- After soaking, use your fingers to carefully lay stamps flat (with the design face up) on a clean and dry paper towel. Make sure the stamps are not touching each other.

- Use another paper towel to cover the wet stamps and gently press on them to blot away any excess water. Don’t use old newspapers to dry wet stamps as the ink can transfer onto the front or back of the stamp and ruin it.

- Once all your stamps are laid out, cover with a piece of paper and sandwich in between some heavy books to flatten them as they dry.

- Leave for between half an hour to an hour, carefully remove them and leave to ‘air’ until completely dry, usually for three to four hours. They are now ready to mount in an album.

- Never attempt to speed up the drying process by placing stamps on a hot radiator or in sunlight because they’ll curl and become damaged.

Stamp Collecting Equipment

Tools that help in handling your stamps:

- Tongs: Tweezers with round ends are used these to handle the stamps. Tongs keep stamps free of fingerprints or smudges. They make it easier to picking up the stamps so you don’t bend them.

- Magnifying Glass: Used to see all the little details of the stamp.

- Stamp Catalogue: Stamp catalogues give you interesting information about your stamps.

Storing Your Stamps

You will need a place to keep your stamps.

- You can make your own album from a loose leaf binder.

- You can print online album sheets –

- Two other ways to store your stamps are Stock sheets (stock books) or Stamp Albums.

- Stock Books hold stock sheets. Each stock sheet has a plastic or glassine cover that holds the stamp in place which allows you to see the stamps. The stamps can then be easily moved around and reorganized.

- Stamp Albums are usually pre-printed so you put the stamp on its preprinted space. There is often information or a caption for the stamps.

Online Resources

Stamp collecting information that can be found on the internet

- American Philatelic Society at stamps.org.

- YouTube Exploring Stamps (and 30 addition Exploring Stamps YouTubes)

- https://stamps.org/news/author/graham-beck/p/1

- https://www.wfscstamps.org/Youth/

- https://classic.stamps.org/Starting-a-Collection

- https://postalmuseum.si.edu/stamp-collecting/introduction-to-stamp-collecting/introduction-to-stamp-collecting.html

- https://www.wikihow.com/Collect-Stamps

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stamp_collecting

- https://www.linns.com/insights/stamp-collecting-basics/growing-a-us-worldwide-stamp-collection.html

- https://www.2-clicks-stamps.com/articles.html

History of Postage Stamps

When the postal service first operated, envelopes and stamps did not exist. People did not like to use envelopes because they made the cost of sending mail more expensive. If you were going to send a letter, you only would have to pay the delivery fees. The fees were extremely high, so many people did not accept letters. Some people even thought of writing secret codes on the outside of the letter that showed the message. The recipient would read the secret message and did not accept the letter so they would not have to pay anything for the message. The postal service began as a system that required the postage be paid first by the sender. This is the beginning of our postage stamps history.

Great Britain issued the first postage stamp on May 6, 1840. It is referred to by philatelists as the Penny Black. Many people purchased the Penny stamp on the first day of issue, not for the purpose of using it on letters but for saving them as historical mementos. These stamps did not have perforations and people would use a scissor to cut each stamp from the page of stamps and use their own glue to keep the stamp on the envelop or letter. Stamp collecting began with the first Penny stamp; it became a very popular hobby in the 1920s.

In 1874, the Universal Postal Union was formed. This allowed member countries to send mail more easily between each other, as the sender did not have to use the stamps of the country to which they were sending their letter.

The use of adhesive postage stamps continued during the 19th century primarily for first class mail. Stamps were denominated with their values (5 cent, 17 cent, etc.). Today stamps issued by the postal service are self-adhesive. Now the United States post office sells non-denominated “forever” stamps for use on first-class and international mail. These stamps are still valid even if there is a rate increase. Adhesive stamps with denomination indicators are still sold.

Postage Stamp Glossary

Adhesive: The glue or paste on the back of the stamp that is used to attach a stamp to an envelope.

Album: A book for storing stamps, it may have printed pictures of the stamps.

Cancellation: A mark used by the post office to show that a stamp has been used. It usually has the date and post office (city, state, and zip code) that cancelled it.

Commemoratives: Stamps issued to honor persons, organizations, events, causes, or on significant anniversaries. They are usually larger in size and often on sale for a limited time.

Definitives: Common postage stamps usually smaller in size and printed in very large quantities. They are available from the post office for a long period of time – possibly many years.

Denomination: Usually the numbers on a stamp that indicate the face value or the amount of postage which the stamp pays. Today many stamps are “Forever” stamps and do not show a value.

Face Value: The actual denomination that is printed on the stamp.

First Day Cover: Envelope with a stamp canceled the first day the stamp was available for purchase.

Gum: Adhesive or paste on the back of the stamp that is used to attach a stamp to an envelope.

Hinge: A thin paper with adhesive on one side used to attach the stamp to the album page.

Margin: The space outside the area of the stamp design. It should be equal on all sides with the stamp design in the center.

Mint: A stamp that has its full gum and has not been hinged. It is in the same condition as it was when originally issued or sold at the post office; it is unused, undamaged, and with full original gum.

Perforations: Holes punched between stamps to make it easier to separate the stamps in a sheet.

Philately: The study of stamps.

Philatelist: A person who studies and collects stamps.

Postmark: A mark indicating when and from where a letter was sent. It may or may not also serve as a cancel, showing that the stamp was used.

Selvage: The margin of a pane (sheet) of stamps that may include the plate number and other markings such as copyright notices.

Topicals: A collection of stamps based on subjects, like dogs, ships, space, and flowers.

Tongs: Tweezers with rounded tips that are used to handle the stamp. They prevent damage to the stamp, including from the oil from the fingers.

Stone Soup – Seeds of Diversity

Diverse Vegetables from the Holiday Folk Fair Community

Stone Soup story is based on an old French folktale

Once upon a time, there was a great famine upon the land. Three soldiers, hungry and weary of battle, came upon a small and poor village. The villagers, suffering a meager harvest and fatigued from the many years of war, saw the three soldiers come upon them. Quickly they hid from sight what little they had to eat, thinking if they seemed unwelcoming the soldiers would move on. They met up with the three at the village square.

A villager walked up to the soldiers and said, “There’s not a bite to eat in the whole province, you’d better just keep moving on to the next village.” The soldier smiled and responded, “Oh, but we have everything we need. In fact, we were thinking of making some stone soup to share with all of you. You, sir, look hungry. We welcome you to share some of our soup.”

“Stone soup! What a ridiculous thing! You can’t make soup from a stone!” cried another villager. However, one of the soldiers gingerly reached into their pocket, and slowly pulled out a smooth, round stone. All three soldiers inspected the stone closely and nodded to one another in agreement.

“We have brought with us a wonderful stone that should make for a great and hearty soup. Do you have a large pot we might borrow to make our stone soup?” asked one of the soldiers. Overcome with hunger and unable to feed the guests staying at his inn, the local innkeeper was intrigued with the idea of making soup from a stone. He pulled a large iron pot from the kitchen of his inn and placed it in the village square. The three soldiers filled it with water, and built a roaring fire under it.

Then, with great ceremony, the three soldiers took the stone they had collected on their travels and placed it into the water. They waited for their stone soup to come to a boil, stirring occasionally with a large wooden spoon.

“Do you know what would really help this soup?” asked one of the soldiers, “A hefty dash of cilantro! You can’t have a good stone soup without cilantro, after all.” A villager replied excited, “Well, I think I might be able to find some cilantro that have you could have, if I would be welcome to share in your stone soup!” The soldiers quickly nodded and assured the villager that there would be plenty of stone soup to go around, and that all were welcome to share in it, with such a large pot of soup on the boil.

By now, hearing the rumor of food, most of the villagers had come to the square or were watching the events of the village square attentively from their windows. As the soldiers fastidiously stirred and sniffed at the “broth,” in anticipation. The hunger of the villagers began to abate their initial skepticism.

“I do like a tasty stone soup,” exclaimed one of the soldiers. “Of course, stone soup with carrots is hard to beat,” he added. “Oh, yes, carrots really add flavor to stone soup,” agreed his companion. “I have some carrots, and you know, I have some corn and cabbage. That would really add flavor and color to this soup, too!” exclaimed another villager. One of the soldiers stirred the soup saying, “Yes, yes, this will be a fine soup, but a pinch of some mushrooms would really make it a soup fit for a king!” A villager listening cried, “What luck! I’ve just remembered where some have been left!”

Luckily this Holiday Folk Fair we’ve been gifted some great vegetables from the different cultures represented at Folk Fair! Let’s see what we have. Maybe some of you already know what some of these are, but hopefully you’ll learn some new ones too! Let’s take a minute to learn where these vegetables came from and how to say their names in their native languages! It looks like we have:

Carrot – Juzra – (root) Persia – Iranian and Afghan

Potato – Patata – – (Underground Stem) – Peruvian

Leek -Genhinen – (stem) – Welsh (national emblem)

Cabbage – Kohl (leaves) – German

Broccoli rabe – Broccoli rabe – (flower) – Italian

Cauliflower – Karfiol – (flower) – Serbia.

Pepper – Pimienata -(fruit) – Mexican

Corn – Maize – (seed) – Native American

Soy beans -Daizu – (seed) – Japanese

Bamboo shoot – Zhusun – (shoots – new growth) – Chinese

Beans – Faswlya – (seed -sprout) – Egyptian

Pasta – Pasta – (grain seed) – Italian

Mushroom – Grzyb – (Fungi) (is not a plant) – Polish

As the “soup” boiled on, the memory of the village improved. In short time, potatoes, peppers, and beans had also found their way into the great pot. When the soup was done, the entire village sat down to a great feast, welcoming their new friends. They all ate and danced and sang well into the night; they were refreshed by the feast and delighting in their newfound friends.

In the morning, the three soldiers awoke to find the entire village standing before them. At their feet lay a satchel filled with the village’s best breads and cheeses. The villagers gathered to say goodbye. “Many thanks to you, for we shall never go hungry now that you have taught us how to make soup from stones!” said one of the villagers. “Rest assured that this is something that we shall never forget and that we shall forever cherish,” said another.

A soldier smiled and said, “Whereas there may be no real secret to stone soup, one thing is certain: It takes many and all to make a great feast.” And with this, the soldiers kindly accepted their satchel of breads and cheeses and went on their way, never to return. It is said that soon after meeting these soldiers, the village quickly returned to its former prosperity, and has thrived ever since. The soldiers are said to still walk from town to town collecting stones along the way, and sharing their secret recipe for their famous stone soup.

By working together, with everyone contributing what they can, a greater good is achieved.

Many plants tell us their stories and play important roles in people’s lives.

What kind of vegetables would you use to make Stone Soup?

Write a recipe for you class’ Stone Soup or your Family’s Stone Soup

This version is from the Portuguese folktale:

A kindly, old stranger was walking through the land when he came upon a village. As he entered, the villagers moved towards their homes locking doors and windows….

Consider this different ending for their story of Stone Soup:

The villager elder offered the stranger a great deal of money for the magic stone, but he refused to sell it and traveled on the next day.

As he left, the stranger came upon a group of village children standing near the road. He gave the silken bag containing the stone to the youngest child, whispering to a group, “It was not the stone, but the villagers that had performed the magic.”

The History of Soup

Soup is an ancient food, prepared for 6,000 years in many different ways around the world. In ancient India, parched barley was ground with juices to make one kind of soup. Ancient Mayans used maize in various liquid foods. Early North American Indians made a broth of hickory nut milk. Yosemite Indians shredded fungi for mushroom soup and also cooked horse chestnut gruel. The Greeks made soups of beans, peas or lentils. Some were made from a black broth of pork, blood, vinegar, salt and seasonings.

Background

In early times, soup was called “pottage” (from pot and the Latin potare, meaning, “to drink”), but by the Middle Ages, the word “soup” had replaced “pottage” in most European languages. The word soup is thought to have come from the sound made by slurping hot liquid from a spoon. Some variations of the word are soop, sopa, sope, soepe, suppa, soppe, soep, suppe, soppa, sopera, soupe, chupe, zuppa, and zup. To sup was to eat the evening meal, at which soup was traditionally served. Eventually the meal itself became “supper.”

As immigrants arrived in the US from countries around the world, they brought their own national soups. German immigrants living in Pennsylvania were famous for their potato soups.

Commercial soup became popular with the invention of canning in the 19th Century. Dr. John T. Dorrance, a chemist with the Campbell Soup Company, invented condensed soup in 1897. Most soups have stock as a base. Stock is made by simmering various ingredients in water, usually for a long period of time. Often the ingredients are less desirable cuts of meat, bones and vegetable trimmings. Herbs and spices add more flavor. The flavor of bone stock comes from the cartilage and connective tissue in the bones. The gelatin in bone broth has many health benefits. Connective tissue has collagen in it, which gets converted to gelatin that thickens the stock.

The use of what to some might appear as trash for making stock—bones and vegetable trimmings, may have been the basis for the old story, “Stone Soup.” Stone Soup is a Grimm Brothers tale in which strangers trick a starving town into giving them some food. The fable is about cooperation amid scarcity. In different traditions, the stone is replaced with other common objects; therefore, the fable is also known as “Button Soup,” “Wood Soup,” “Nail Soup,” and “Axe Soup.”

Traditional Foods: Remembered and Shared

‘Tis the season to celebrate with friends and family, and of course with good food! The most wonderful time of the year is made extra special with family heritage recipes, from latkes to gingerbread, from mochi to Pan de Muerto, from Thanksgiving turkey to lentils.

What’s the Secret? Spices, Herbs and Flavorings

“Grandmothers are the keepers of the culinary flame, especially for immigrant families,” says Patricia Tanumihardja, author of the recipe-packed, story-filled The Asian Grandmothers Cookbook (Sasquatch Books). “Language and food are the two most important ways that culture is passed down through the generations.”

She believes strongly that immigrant grandmothers are the torchbearers of a family’s culinary heritage. “Grandmothers are the closest link to an immigrant’s homeland. They cook for their grandchildren, and they speak to them in their native tongue.”

Immigrant Spices and Spices the Immigrants Brought

Some of the spices we use today have been used for thousands of years. Spices were mentioned in hieroglyphics on the wall of Egyptian pyramids. The Queen of Sheba went to visit King Solomon in Jerusalem and brought him gifts of valuable spices. Adventurous traders took spices from India to Egypt; it was a dangerous trip because pirates waited to rob ships of their precious spices.

In spite of the cost, spices were in great demand. To understand the reasons for this, think of the condition of food in those days. There was no refrigeration and beef was killed in fall and salted to preserve it. A dash of pepper or other sharp tasting spice mixed with the worst food made it easier to eat; pepper hid the bad odor and taste of decayed cooked meat. Spices also kept meat fresher. Only nobles could afford to pay great sums of money for a pound of pepper to conceal the spoiled taste. Ordinary people had to eat unappetizing food or go hungry.

There was no plumbing or sanitation. Their clothing and houses could not be kept fresh and clean. Therefore they used strong herbal scents.

Spices were also popular with doctors as medicines like cinnamon for curing pain and strengthening the heart, and cloves and nutmeg for curing almost anything.

Even as hygiene and sanitation improved, herbs continue to be used in cooking, medicine and for general household use.

Spices were immigrants, too. Immigrants often brought their spices with them so that they could flavor their foods that reminded them of their homelands. Spices gave variety to the simple daily foods. They also used them as medicines.

Look at the grocery shelf and see the variety of spices we have available. It is hard to believe that long ago, these spices are the same spices that caused war, made great fortunes, were pirated, brought adventure and discovery and became businesses. Today more than five hundred ships a year bring spices to the United States.

The most popular spices came from the Orient: pepper, cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves, and ginger. Other spices are herbs such as seeds from anise, cumin, fenugreek, sesame, fennel, cardamom, poppy, leaves from sage, chives, marjoram, thyme, basil, mint, rosemary, parsley, and turmeric which is a root and saffron from the stigma of the crocus flower. Saffron is still the most expensive spice. Laurel wreathes were the prizes at the Olympics; they were made of bay leaves.

Suggested Activities

Find out what spices your family uses. Where do they come from? Which family member brought them to your family? How is the spice used? What herbs and spices are grown in your yard?

Research the history of spices and the pirates who plundered ships to get these expensive products.

On a map, locate the major sources of spices.

Find out how different spices are used. What is used for illnesses like mint tea, ginseng, garlic, onions, caraway seed.

Visit the herb gardens in Whitnal Park.

A Short History of Spice Trading

Spices and herbs have played a dramatic role in the development of Western civilization. Spices today are plentiful and are used mostly as flavorings. However, in ancient and medieval times, they were rare and precious products, used for medicine, perfume, incense, and flavoring.

3000 BC to 200 BC

Arabs traded spices and herbs. Caravans risked dangers in carrying spices.

200 BC to 1200

The Romans control the trade.

1200 to 1500

Europeans explore passages to the East Indies.

The 15th to the 17th Centuries

Wars for control of the spice trade break out.

The 16th to the 18th Century

English exploration begins.

The 17th to the 20th Century

Americans enter the spice trade.

Spice Geography

Overview:

This lesson encourages students to think about where the ingredients in their food come from and how they are produced. Students will investigate the origins of a variety of spices from around the world and map these locations. They will then research and create presentations describing the climate, terrain, and agricultural practices in the places they have mapped.

Connections to the Curriculum: Geography, agricultural science

Connections to the National Geography Standards:

Standard 11: “The patterns and networks of economic interdependence on Earth’s surface”

Standard 16: “The changes that occur in the meaning, use, distribution, and importance of resources”

Time: Three to four hours

Materials Required:

- Computer with Internet access

- Blank Xpeditions outline maps of the world, one for each student

- International cookbook

Objectives:

Students will…

- look at recipes from six continents, and list the spices used in the recipes;

- look up the spices in an online spice encyclopedia and map the places where the spices originated;

- research and take notes on the climate, terrain, and agricultural practices of the places they have

mapped;

- discuss the results of their research; and

- create posters, multimedia presentations, or written reports describing the agriculture in the countries they have mapped.

Geographic Skills:

- Acquiring Geographic Information

- Organizing Geographic Information

- Answering Geographic Questions

- Analyzing Geographic Information

S u g g e s t e d P r o c e d u r e

Opening:

Ask students what types of spices they enjoy in their foods. Do they know where these spices come from?

Development:

Have students find at least one recipe from each continent (except Antarctica, and they should find two from different parts of Asia) on the Web or in an international cookbook.

Ask students to list the spices used in the recipes. Provide some examples of spices: e.g., cinnamon, oregano, and ginger.

Have students look up these spices at Spice Advice’s Spice Encyclopedia or McCormick’s Enspicelopedia and map the places where the spices originated on blank Xpeditions outline maps of the world.

Have students research and take notes on the climate, terrain, and agricultural practices of some or all of the places they’ve mapped (depending on your time frame) to find out what it might be like to cultivate these spices.

Closing:

Discuss with the class what they have learned in this activity. Do they tend to think about where their food ingredients come from? Do they tend to think about who produces the food and who works on the farms? Why might it be a good idea to have this information about their food, and why is it uncommon to know these things?

Suggested Student Assessment:

Have students create posters, multimedia presentations, or written reports describing what agriculture is like in the countries and regions they have mapped. You might want to assign specific places so that each student has one place to investigate and all places are represented throughout the class.

Extending the Lesson:

Have students conduct research to learn about the development of the spice trade during the Age of Exploration. Which spices became popular in Europe, where did these spices come from, and what methods were used to extract the spices from their places of origin?

Is it an Herb or a Spice?

We often use the words herb and spice interchangeably. Herbs and spices are obtained from plants. (Salt is neither a spice nor an herb. It is actually a mineral.) Herbs and spices are used primarily for adding flavor and aroma to food. And both are best used fresh but can be saved by drying. While there are similarities, there also are subtle differences between herbs and spices.

Herbs are obtained from the leaves of herbaceous (non-woody) plants. They are used for savory purposes in cooking and some have medicinal value. Herbs often are used in larger amounts than spices. Herbs originated from temperate climates such as Italy, France, and England. Herb also is a word used to define any herbaceous plant that dies down at the end of the growing season and may not refer to its culinary value at all.

Spices are obtained from roots, flowers, fruits, seeds or bark. Spices are native to warm tropical climates and can be woody or herbaceous plants. Spices often are more potent and stronger flavored than herbs; as a result they typically are used in smaller amounts. Some spices are used not only to add taste, but also as a preservative.

Some plants are both herbs and spices. The leaves of Coriandrum sativum are the source of cilantro (herb) while coriander (spice) is from the plant’s seeds. Dill is another example. The seeds are a spice while dill weed is an herb derived from the plant’s stems and leaves.

Examples of Herbs

- Thyme

- Sage

- Oregano

- Parsley

- Marjoram

- Basil

- Chives

- Rosemary

- Mint

Examples of Spices

- Cinnamon – bark of the cinnamon tree

- Ginger – root

- Cloves – flower bud

- Saffron – stigma (female reproductive part) of saffron crocus

- Nutmeg – seed

- Vanilla – undeveloped fruit of an orchid

- Cumin – seed

~ Foy Spicer, Department of Horticulture – 8/22/2003

The First People and The Hoop Dance

Shanley now helps bring healing, storytelling and reclamation to people from all over the world through her gifts of dance, educational YouTube videos, her writings, powwow fitness and hoop dance classes and public speaking.

Shanley now helps bring healing, storytelling and reclamation to people from all over the world through her gifts of dance, educational YouTube videos, her writings, powwow fitness and hoop dance classes and public speaking.

Shanley is a prominent figure in her community having influenced many people to become agents of change in their own lives and within their communities, to reclaim culture, create awareness and elevate the world through her actions. Shanley is a strong advocate for sustainable intentional living, reclamation, spiritual and cultural practice and unconditional love for all beings.

Centuries ago, it is estimated that 10,000 Potawatomi people occupied and controlled approximately 30 million acres of land in the Great Lakes area. They migrated west with the Ottawa and Ojibwe tribes who were also Algonquian-speaking, Woodland peoples. The Potawatomi migrated and settled along the shores of Lake Michigan – “a large body of water” in what is now called Milwaukee – “good land” or “a gathering place by the river” – which became a popular meeting place or council ground for different tribes of Indians.

The Ojibwe stretch from present-day Ontario in eastern Canada all the way into Montana. Oral traditions of the Ojibwe, Ottawa, and Potawatomi assert that at one time all three tribes were one people who lived at the Straits of Mackinac. From there, they split off into three different groups. Linguistic, archaeological, and historical evidence suggests that the three tribes do indeed descend from a common ethnic origin. The three languages are almost identical. The Ojibwe call themselves “Anishinaabeg,” which means the “True People” or the “Original People.” Other Indians and Europeans called them “Ojibwe” or “Chippewa,” which meant “puckered up,” probably because the Ojibwe traditionally wore moccasins with a puckered seam across the top.

By the end of the 18th century, the Ojibwe controlled nearly all of present-day Michigan, northern Wisconsin, and Minnesota, including most of the Red River area. They also controlled the entire northern shores of lakes Huron and Superior on the Canadian side and extending westward to the Turtle Mountains of North Dakota. In the latter area, the French Canadians called them Ojibwe or Saulteaux.

From: Milwaukee Public Museum

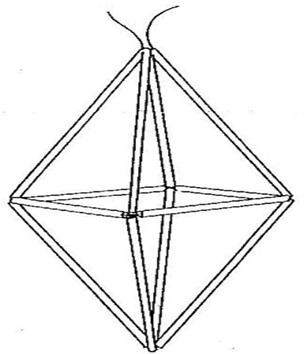

Lithuanian Straw Ornament – Plastic Straws

Lithuanian Straw Ornament – Plastic Straws

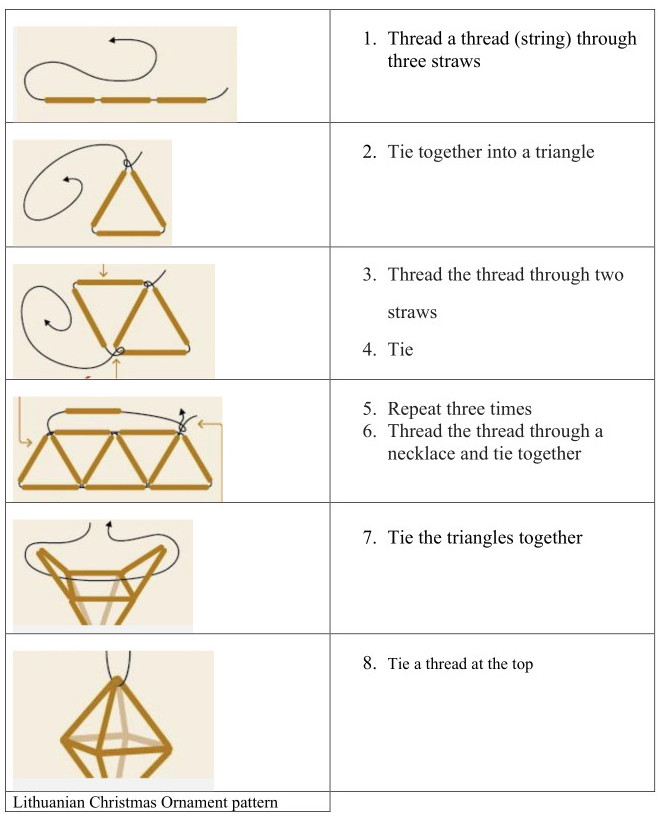

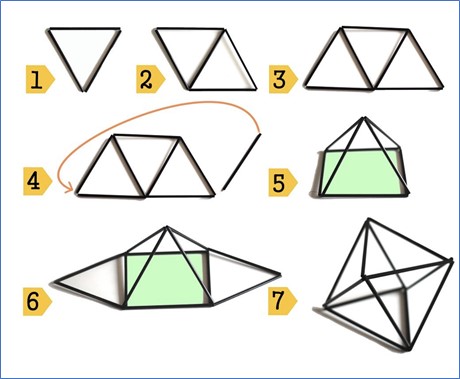

Dry, ripe wheat or rye stalks are selected to make these Lithuanian ornaments. Today many crafters use white paper or plastic drinking straws to make ornaments.

Each country around the world has its own Christmas traditions. Lithuanians and Germans often used straw to create ornate decorations and ornaments for their Christmas trees. If you’d like to make your own traditional straw Christmas tree decorations, you can use drinking straws and these instructions.

Cotton thread or string is used for threading. Long medium width needles are used to pass easily through the hollow centers of the straws.

Threading usually starts with basic two-dimensional shapes, beginning with triangles and working up to multi-dimensional constructions.

MATERIALS:

- Straw, prepared as above, or white plastic drinking straws

- String or thread (lightweight kite thread or other sewing thread)

- Needle (one short and one very long)

- Ruler

- Scissors or cutting blade

General Instructions

Cut twelve 4-inch lengths of straw.

Cut 6 feet of string, and thread needle.

Thread a needle and keep the string as a single strand while working the entire ornament. If additional string is required, remove the needle and attach more string, rethread and continue.

Pull the needle through straws of equal length (see diagrams), tie a knot at the end of the last straw, pull it inside the straw to hide it, leaving enough string to continue with the rest of the ornament.

If you look on the internet for “Lithuanian Straw Ornaments,” you can see some of the most beautiful and intricate ornaments. You may also get ideas of different types of straw stars you can make.

E-mail Sign up

Sign up here to receive updates, notifications, and special information about Holiday Folk Fair International.

Holiday Folk Fair International

1110 North Old Third Street, Suite 420

Milwaukee WI, 53203, USA

Phone: 414-225-6225 • 1-800-FAIR-INTL • Email: info@folkfair.org